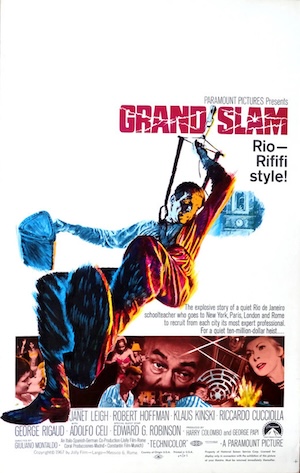

1967’s Grand Slam belongs to two overlapping traditions. First, it’s an international heist movie, in good company with The Italian Job, Topkapi, and The Great Train Robbery. Second, it’s one of those European productions where the top-billed stars turned up for a day’s work and a paycheck, and are promptly never seen again. It’s easy to envision Ray Milland in the Edward G. Robinson role, if this was made in the 1970s.

We open with Edward G. Robinson, recently retired from 30 years of teaching at a Catholic school in Rio de Janeiro, dropping in on his old friend Adolfo Celi (dubbed, but not by Robert Rietty), now in the rackets. Robinson, as one does, has spent the last 30 years developing the perfect plan to steal $10 million in diamonds from the building across the street from the school, and he needs Celi to provide the team.

Compared to other heist movies the team is small. We have Robert Hoffmann as a French playboy, Klaus Kinski as a German ex-soldier, Riccardo Cucciolla as an Italian mechanical engineer, and George Rigaud as an English safecracking expert. Cucciolla makes toys for a living; Rigaud is a manservant; he cracks safes on his holiday.

Hoffmann’s job is to seduce Janet Leigh, working as a secretary at the firm, and steal her key to the vault. The plan is that the key is only gone for an hour, so that it won’t be missed. Meanwhile, Cucciolla and Rigaud will defeat the various safeguards protecting the vault. The return plan involves flushing the key down a toilet at the heist scene, to be intercepted by Kinski, who’s crawling around in the sewers. In the backdrop of the entire heist? Rio Carnival, looking much more vibrant than it will in Moonraker.

The plot unfolds along two tracks. On one, Hoffmann trying, with difficulty, to seduce Leigh, with the end goal of being in her apartment the night of the heist so that he can steal the key. The key doesn’t have the same reality of the Chubb keys in the The Great Train Robbery. On the other, Kinski, Cucciolla and Rigaud conduct reconnaissance and prepare for the actual cracking of the safe.

The plot drags a bit and I feel like we arrive at the heist without the right staging. I think we really miss the walk-through/dress-rehearsal scene that other heist movies have, giving you a sense of what’s going to happen (so that you know when things don’t go quite right). Brian de Palma’s 1996 Mission: Impossible, borrowing from Topkapi, does an excellent job of this.

The heist itself is extremely well done. No extraneous sound of any kind. The Ennio Morricone score takes a smoke break. At one point Cucciolla and Rigaud don infrared goggles so that they can deploy a pneumatic trestle to bypass photocell beams. I have qualms about other parts of the movie; not here.

The ending comes somewhat out of left field with a pair of double-crosses. Our protagonists have stolen the diamonds and are looking to make good their escape, and it all falls apart. Rigaud is killed at a police checkpoint. Kinski murders Hoffmann while disposing of Rigaud’s body, and then leads Cucciolla into a police ambush. Kinski looked sweaty throughout the whole movie, but he always does, and it wasn’t at all telegraphed. Now the sole survivor, Kinski is murdered by Adolfo Celi, surprisingly returning to the movie for another scene. But! The case is empty; the diamonds are gone…

We’re in Rome. I’d half-suspected another shoe dropping with Leigh’s character and we get it, as she meets up with Robinson in the shadow of the Colosseum. Leigh was in on it from the beginning and switched cases. It’s not really clear how, and the movie doesn’t linger on the point. Just as we think the movie’s over, a random motorcycle thief rips off the diamonds and zooms away. The credits roll as Robinson and Leigh look on, agape.

I liked this but I’ve seen every element done better in a different film. Either version of The Italian Job, Topkapi, The Great Train Robbery, The Return of the Pink Panther. Silver Bears isn’t exactly a heist movie but it hits some of the same notes. Some of it is technical–the dubbing lets down the foreign cast, the matte work in Edward G. Robinson’s scenes is noticeably bad. Some of it is plot driven–I don’t really buy the twists in the third act, and they don’t fit with a tone that hasn’t been all that light-hearted.

If you’ve nodded along at every film I’ve mentioned to this point, then watch this one too.